Looking for more?

Download our guide on how to prepare agricultural financial statements.

DownloadIn today’s competitive agricultural, forestry and fisheries environments, it's critical to understand the financial performance of your business.

As a tool for management

Successful managers use financial statements in combination with production records to identify strengths and weaknesses in their operation. In addition to tracking trends in assets and liabilities, financial statements can reveal where revenues are originating and where expenses are occurring. Financial statements can be used to time cash expenditures and plan for credit needs. Finally, these statements provide the critical data for ratio analysis and benchmarking.

As a tool for use with lenders and other professionals

Lenders request, and in most cases require, an accurate set of financial statements to accompany a credit request. A carefully prepared set of financial statements shows you have a detailed understanding of your business and its repayment capacity. Others, such as attorneys and financial planners, also need financial statements for services such as estate and retirement planning, organizational establishment and buy-sell agreements for business transition purposes.

As a tool for tax compliance

A carefully prepared set of financial statements can make life much easier when tax time comes around.

This prevents last minute information collection and provides peace of mind in an IRS audit. Financial statements can be prepared by individuals, in-house employees or accountants. Statements prepared by accountants will range from simply compiling a business owner’s numbers, to reviewing and reconciling numbers, to a formal, unqualified audit. Even if you have an accountant that keeps your operation’s books and prepares your taxes, it’s still important to understand how financial statements are prepared. Although accountants are professionals and are knowledgeable in their field, no one understands your business like you do.

Financial statements include the balance sheet, income statement, statement of owner equity, statement of cash flows and cash flow projection. Our discussion will focus on the three most commonly used financial statements: the balance sheet, income statement and cash flow projection. Financial statements are interrelated; therefore, proper timing of the statements is important to gain the most benefit.

Balance Sheet

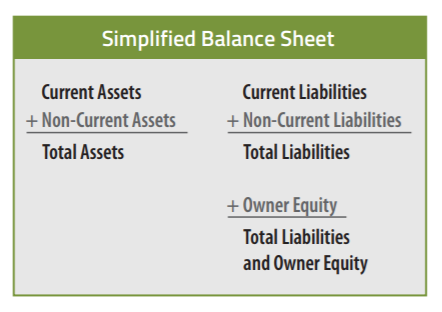

The balance sheet is a statement of financial position at a specific point in time or a financial snapshot of the business. The balance sheet reflects the result of all past transactions but not how the current financial position was obtained. The balance sheet consists of three main parts:

Assets

Assets include anything that is owned by the entity that has monetary value. Standard accounting practices value assets at either cost, market value or the lower of the cost or market, depending on what is preferred by the person preparing or requesting the balance sheet. Assets valued on a cost basis are listed at the historical cost less any accumulated depreciation. Market valued assets are listed at fair market value based on the asset’s condition, location or other relevant factors. Assets should be separated into two categories: current and non-current. A more detailed discussion of asset classification will follow.

Liabilities

Liabilities include all claims against the business by creditors, suppliers or any other person or institution to which a debt is owed. Liabilities, like assets, are classified into current and non-current categories.

Owner equity

Owner equity, or net worth, is the difference between total assets and total liabilities. It reflects the owner’s stake in the business and includes investment capital and retained profits. In a corporate business structure, owner equity will include stockholder’s equity, additional paid-in capital and retained earnings.

Current Assets

Current assets are the first classification of assets appearing on the balance sheet. Current assets include items such as cash or assets that can and will be turned into cash within a year without disrupting normal business operations. Current assets also include any items that will be consumed within a year. Examples of current assets include:

Non-Current Assets

Assets that support production activities and are considered to have a life greater than one year. In agriculture, common non-current assets include machinery, equipment and breeding livestock. Another major category of non-current assets is real estate, including land, buildings and improvements.

If a personal balance sheet is prepared, non-current personal assets may be included, such as household furnishings and equipment, personal and recreational vehicles and personal retirement accounts. Personal property may also be included if the balance sheet is prepared for a consolidated entity.

Liabilities

Similar to assets, liabilities are also classified as either current or non-current. The liability section of the balance sheet should include all obligations (classified based on repayment schedule) as of the date of the balance sheet

Current liabilities

All debts and obligations that are due within the next 12 months. Examples of some common current liabilities are:

Non-current liabilities

Non-current liabilities capture all obligations that are due and payable beyond one year. The most common noncurrent liabilities are term loans used to finance machinery, equipment, breeding livestock or real estate. The portion of the term loan due beyond 12 months is considered a non-current liability. Remember the principal amount due within 12 months is a current liability.

Contingent liabilities

Another category of liabilities is contingent liabilities, which includes such items as guarantees, pending lawsuits, and federal and state tax disputes. Common contingent liabilities also include student loans or car loans co-signed by parents. These items appear as footnotes to the balance sheet and are not liabilities at the present, but the potential for an obligation exists.

Owner Equity

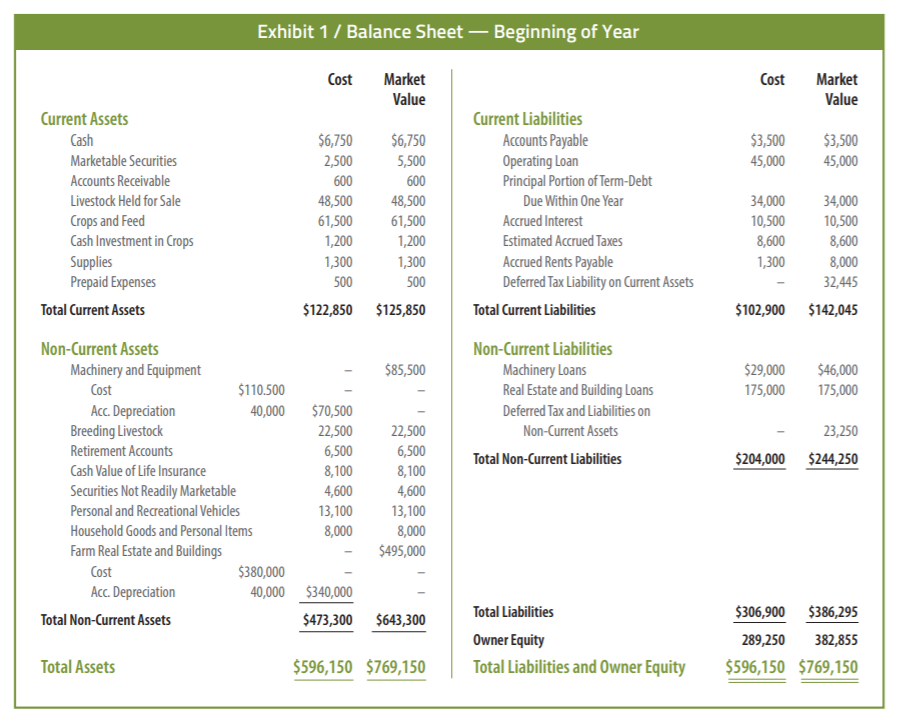

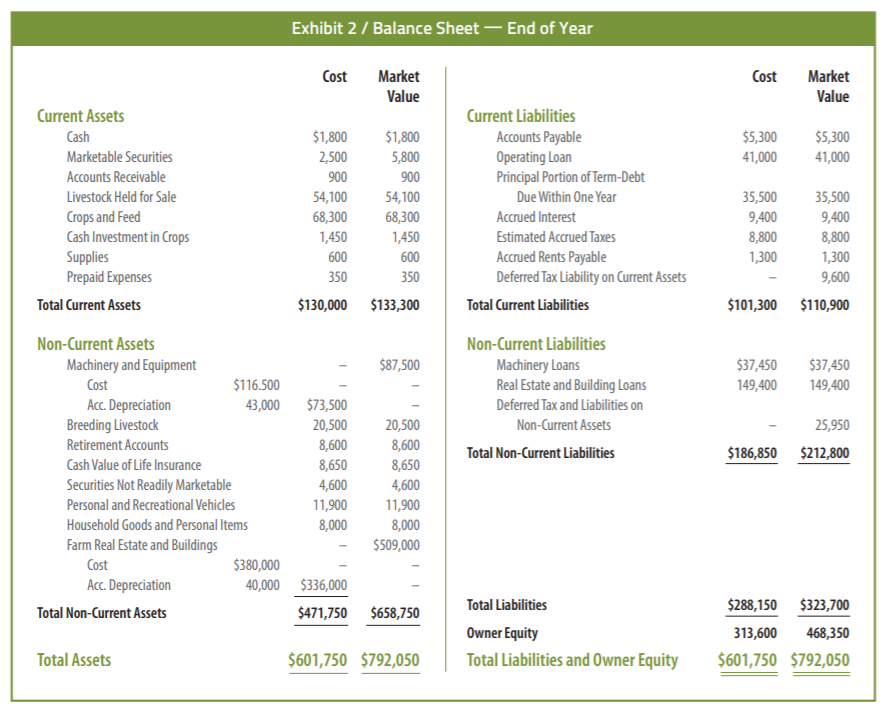

Owner equity is a residual amount after liabilities are subtracted from assets (see Exhibit 1 below and Exhibit 2). Owner equity reflects the owner’s investment of capital into the business and retained earnings which are generated over time. Retained earnings are profits that have been reinvested back into the business rather than withdrawn by the owners or paid out in dividends in the case of a corporation.

Balance sheet considerations

The ownership structure of agricultural businesses is becoming increasingly complex. The traditional sole proprietorship is no longer the norm in agriculture. Combinations of partnerships, corporations and limited liability companies are quickly emerging with one entity holding operating assets and another entity controlling the capital assets. It is essential to identify the entity for which the balance sheet is being prepared, such as business, personal or a consolidation of both.

Timing

For analysis purposes, the timing of the balance sheet is important. Balance sheets are most useful when they consistently coincide with the timing of the income statement, usually at fiscal year-end, which is typically the end of the income period. The accrual adjusted income statement (discussed later) combines other data, including changes in the beginning and end-of-year balance sheets.

Asset valuation

A balance sheet is only as valuable as the quality of the information used to prepare it. When valuing assets on a market basis, a conservative approach is preferred, based upon appraisals and recent sales data in the market. When preparing a balance sheet, it’s important to distinguish between possession and ownership of assets. If a partial interest in property is owned, then only that portion should be reflected as an asset on the balance sheet. Ownership issues also arise in the case of “life estates” and lease agreements.

When crop and livestock inventories are included on the balance sheet they should be accompanied by a schedule detailing the amount and value of each item, indicating how the total value was derived.

Often a person is involved in more than one business venture. If so, information about assets and liabilities associated with other businesses should be identified. One business may show significant equity while another is heavily leveraged. Lenders are likely to request a consolidated balance sheet that combines all business and personal assets and liabilities.

Valuing leases

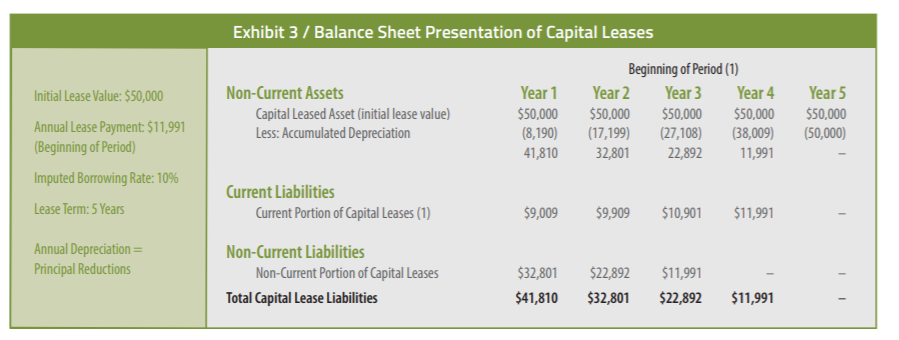

Numerous valuation issues arise when preparing balance sheets which exceed the scope of this discussion. One issue is that of capital leases for items such as tractors, combines, irrigation equipment and storage structures. In the past, many lease obligations were simply included as footnotes to the balance sheet. However, these types of leases should be included on the balance sheet.

There are two general types of leases: operating leases and capital leases. Operating leases allow the lessee the right to use an asset for a relatively short period of time. Most operating leases should appear as a note to the balance sheet (unless prepaid or past due), similar to the rental of farm land. A capital lease is a direct substitute for purchase of the asset with borrowed money. It transfers substantially all the benefits and risks inherent in the ownership of the property to the lessee.

Exhibit 3 illustrates an example of a five-year capital lease agreement with annual payments (due at the beginning of the period) of $11,991. The lease is treated similar to an equal payment, amortized loan and must be reflected as both an asset and a liability on the balance sheet. Although there is no interest rate stated in the agreement, an $11,991 annual payment for five years at an “imputed interest rate” of 10% results in a present value of $50,000. This is the initial lease value (both asset and liability). Remember, it’s the lease investment which is being put on the balance sheet, not the asset being leased.

Also in Exhibit 3, the asset is listed as a non-current asset each year. The principal due within the year and any accrued interest as of the date of the statement are listed as current liabilities, and the remaining lease obligation is a non-current liability.

Deferred taxes

As discussed earlier, assets can be valued on the balance sheet, either on a cost or market value basis. A market value balance sheet reflects the impact of deferred tax liabilities (refer back to Exhibits 1 and 2). Deferred taxes are the federal and state taxes that would be incurred if the business was liquidated. Deferred taxes on current assets arise because many agricultural producers report income on a cash rather than accrual basis for income tax purposes. Therefore, they do not pay taxes on the accumulation of crop and livestock inventories over time. Income taxes would be due if inventories were sold and if the expenses associated with them had previously been deducted as cash expenses. Deferred taxes may also be present on non-current assets. Two examples of deferred tax situations are:

Income statement

A business income statement, also called a profit and loss statement, is used to measure revenues and expenses over an accounting period. Unlike the balance sheet, which reflects the financial position at any given point in time, the income statement shows income and expenses for a period of time, usually one year. Income statements can be used to determine income tax payments, analyze a business’ expansion potential, evaluate the profitability of an enterprise and assist in loan repayment analysis.

Identifying the entity

Identifying the business entity is also important when preparing an income statement. The income statement should be prepared for the same entity as the balance sheet, either business, personal or consolidated. Because of the interrelationship between the balance sheet and income statement, the time period covered by the income statement should be the time between the beginning and ending balance sheets. The most common period is annually, although quarterly or monthly statements are sometimes desired.

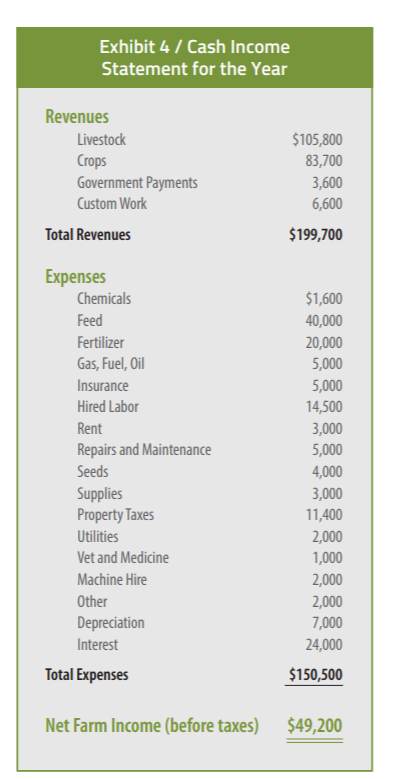

Revenues and expenses

All income statements include two categories: revenues and expenses. However, income statements can be prepared two ways, depending on how revenues and expenses are derived. A cash income statement measures revenues only when received and expenses only when paid. An accrual income statement measures revenues when generated and expenses when incurred, whether or not cash actually changes hands. The cash income statement (illustrated in Exhibit 4) is the easiest to prepare but is inadequate for measuring true profitability because it fails to match the timing of income and expenses.

Depreciation

Depreciation, although not a cash expense, is included on both the cash and accrual income statements as a way of spreading the cost of capital purchases over their useful life. Accelerated depreciation is frequently used for tax purposes. If this is the case, it should be noted that accelerated depreciation is being used, because it could distort profitability.

Schedule F

The Schedule F tax form is often used as an income statement. Although the Schedule F can offer some valuable insight, it is not an income statement and should not be used as such. However, in some cases it can be used effectively if three to five years of information is provided and the business is in a stable operating mode with no major adjustments. Using a series of Schedule Fs as an income tax statement rests on the assumption that shifting income and expenses will even out over the years.

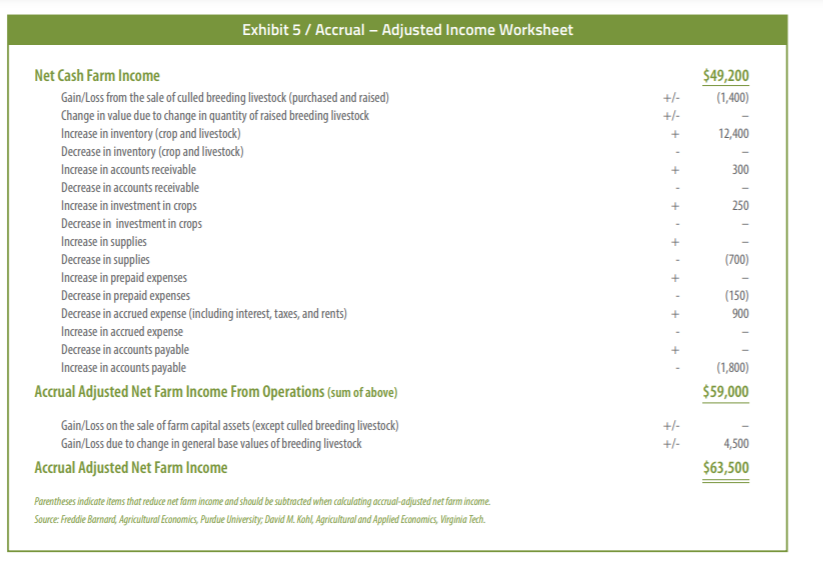

Accrual-adjusted statements

The Farm Financial Standards Council recommends the use of an accrual-adjusted income statement. Ideally, a business’ accounting records will produce an accrual statement; however, in practice, adjustments are made to the cash income statement (or Schedule F) to gain an accrual-adjusted income statement.

Exhibit 5 below illustrates how accrual adjustments are made. To convert cash income to accrual adjusted income, we must look at changes between the beginning-of-year and end-of year balance sheets. Adjustments to revenue include changes in inventories and accounts receivable. In the expense section, adjustments are made for changes in unused assets, prepaid expenses, accrued expenses and accounts payable. Gains or losses on the sale of capital assets are also added or subtracted.

Revenues and expenses can come from a variety of sources in an agricultural business. Categories of revenues that are usually included in an income statement are:

Expense items included on the income statement vary with the type of business but include all operating expenses, interest and depreciation.

Cash flow projection

The balance sheet and income statement provide present and historical financial information that reflect past financial performance of a business. However, producers and lenders are often equally, if not more, interested in future performance. For this reason, a cash flow projection is a valuable financial tool.

A cash flow projection summarizes cash inflows and outflows over a given period. A projection can be prepared for the business, individual or a consolidation of both, similar to the balance sheet and income statement. The cash flow projection can be useful for preparing projected income statements and balance sheets and for determining:

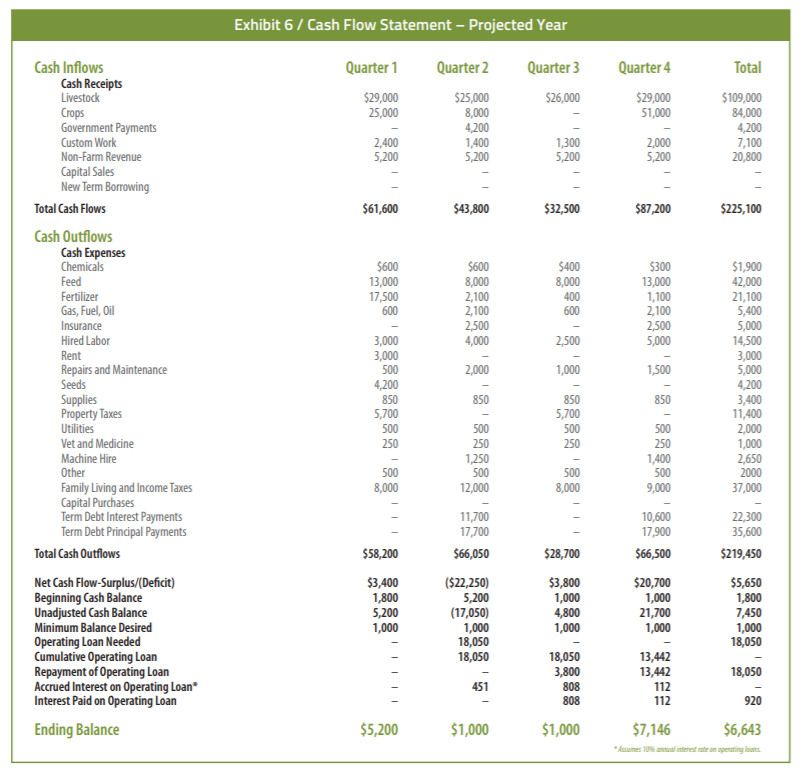

Components

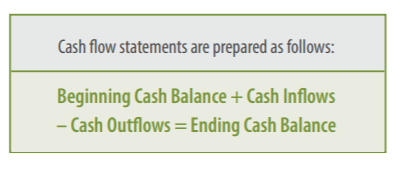

While cash flow statement formats can vary, there are three basic components: cash inflows, cash outflows and operating finance activities. Exhibit 6 on the next page illustrates a cash flow projection. Cash inflows include receipts from farm and nonfarm activities that are divided into relevant categories for the type of business being examined. Cash outflows include a detailed listing of cash expenses as well as principal and interest payments on term debt.

Different scenarios

A one-year projection can be completed for different scenarios to examine price, cost and related impacts.

Cash flow projections for multiple years may also be useful when development is being done, in order to project cash needs prior to full production or adequate production to break even.

Different cash flow scenarios may include: “How would cash flow be affected if commodity prices were 50 cents lower than expected?” or “What is the impact of a 10 percent increase in fertilizer costs?” Testing these options helps identify how sensitive an operation or projected scenario is to changes in the market environment. It’s important to remember a cash flow projection is only as good as the assumptions and information used to prepare it.

Whether you are preparing your own statements, or analyzing those prepared by an accountant, this publication should provide a good basic understanding of how to prepare financial statements that are valuable both internally as a management tool, and externally for use with outside professionals.